The 2016 Budget could be the last chance for the government to redeem itself and find a way back into the common man’s heart.

It is that time of the year again. Newspapers, business channels, Internet sites are all full of ideas, suggestions and even advice for Finance Minister Arun Jaitley. The minister’s appointment diary is brimming with meetings scheduled with representatives from industry, trade unions and agriculturalists. They all come armed with wish-lists, hoping to influence the final design of this year’s Budget exercise.

Jaitley is on track to present his third budget (for 2016-17) and, while patiently sticking to the routine of meeting various lobbies and representatives, he is aware of the criticism he faced for his first two Budgets and the challenges that lie ahead. It’s now or never; this might be his last opportunity to introduce bold reforms and sow the seeds of future growth. Next year might be too late; assembly elections for Uttar Pradesh and Punjab among other states are scheduled for 2017 and expedient politics traditionally triumphs sensible, hard-nosed economic measures in poll-bound years; the year also marks the beginning of the countdown to 2019 general elections.

To be fair, the FM does seem trapped in a cleft stick. Look at the hand he has been dealt: the global economy is struggling to emerge from a prolonged slowdown, leading to lower demand for Indian goods and services, and shrinking exports; China’s economic recalibration is spooking global capital flows and skewing the pitch for foreign direct investment (FDI) into India; indiscriminate past lending by banks (largely public sector banks) has impaired their ability to finance new projects, especially infrastructure projects; power generation and supply — essential for manufacturing activity — is stuck in a tangle of issues relating to fuel supplies, pricing, past regulatory infractions; agricultural output remains depressed due to sub-par monsoons, in addition to legacy issues of low productivity, inadequate credit and input supplies; this has dampened rural demand, thereby impacting a wide range of industries.

In addition, the pre-election promises of fortifying the country’s manufacturing base, resulting in additional employment, fanned unrealistic expectations; when these did not materialise (as they were not expected to in such a short period), they spawned widespread disappointment with the regime’s economic managers.

It might be instructive to review the FM’s first two Budgets to decipher the tenor and direction of this government’s economic policy-making. In his debut (Budget 2014-15) innings, presented 45 days after taking office, the focus seemed to be on long-term, structural reforms: FDI up to 49 per cent in defence and insurance, guarantees of a stable and predictable tax regime, real estate and infrastructure investment trusts, incentives for foreign institutional investors (FIIs) and fillip to debt markets. The second outing continued policy thrust in the same direction: greater decentralisation and balanced regional growth through higher devolution to states, commitment to increased public expenditure to kick-start investment in the economy and a host of institutional reforms to attract fresh domestic and foreign investment.

But, expectations built up in the pre-poll season cannot be wished away easily and stakeholders have started voicing their disappointment. In short, Jaitley has to find ways to prod the economy into a higher growth trajectory immediately, without over-playing his hand or pushing the economy down a fiscal slope. On the other hand, the government is committed to certain expenditure — social sector allocations (especially in a year of agricultural distress and depressed rural incomes), a higher outgo because of Seventh Pay Commission recommendations and One Rank One Pension settlement (both are expected to result in combined outflows of about Rs 100,000 crore), interest burden on past government loans, capital infusion for state-owned banks and other PSU companies, plus a host of other obligations.

The Good News

Fortunately, revenue growth has been good. Data from the Controller General of Accounts shows net tax revenue for the first eight months (April-November) at Rs 4,64,864 crore, a growth of 12.5 per cent over the corresponding period last year. Non-tax revenues rose 35 per cent, helped primarily by spectrum auction proceeds and transfer of profits from public sector companies. There are three reasons behind tax revenue growth — higher duties on petroleum goods, the new service tax rates and the enhanced cess.

There are other encouraging signs as well. Bursts of public expenditure during June, July and September have taken the government’s total planned capital expenditure to Rs 97,788 crore during the first eight months of 2015-16, a 57 per cent jump over what was spent during the corresponding period last year. For example, funds allocated during 2015-16 to states and Union Territories for development of national highways, according to a PIB press release, is significantly higher than previous year: Rs 81,006.99 crore against Rs 31,495.20 crore in 2014-15, a jump of over 157 per cent. It remains to be seen how much of that allocation is actually spent. The National Highways Authority of India has so far awarded 43 projects in the current financial year for a total length of 2,624 kms.

The individual ministry-wise data provides greater insight. The ministries of road transport and highways, and rural development are among heavy-hitting ministries, with both having exhausted 74 per cent and 80 per cent of their budgeted plan expenditure for 2015-16 in eight months. Even the ministries of agriculture, health and family welfare and human resource development have spent a higher proportion of their budgeted plan expenditure than last year. More pointedly, among the large spenders seem to be ministries charged with key social sectors — such as, rural development and health.

Clearly, the government is betting on higher public expenditure to shake the economy out of its torpor. This is classic text-book stuff. It is also in keeping with the FM’s undertaking in last year’s Budget speech to increase public investment outlay: “The total additional public investment over and above the RE (revised estimate) is planned to be Rs 1.25 lakh crore, of which Rs 70,000 crore would be capital expenditure from budgetary outlays.”

Clear & Present Dilemmas

The proverbial monkey-wrench is lack of revenue to finance public projects. While revenue generation has so far held up, largely on back of indirect taxes, there are multiple pressure points building up.

One, industrial activity as represented by the Index of Industrial Production shows 3.9 per cent growth during April-November 2015 over the same period last year, helped in large measure by festival shopping during October. Three among the top five items which contributed to October growth corroborates this — gems and jewellery, telephone instruments (including mobile phones) and passenger cars. On the flip side, what is worrying is stagnation in consumer non-durable items, which shrank by 0.5 per cent during April-November. In fact, consumer non-durable items stayed in negative zone in five of the eight months. In addition, the Nikkei Purchasing Managers’ Index also indicates manufacturing shrinking in December, affected partly by the Chennai floods.

Two, the continuing fall in exports — close to 20 per cent by November — and its impact on overall manufacturing activity, is likely to dampen revenue generation in the coming fiscal. Worryingly, commerce secretary Rita Teotia was widely reported informing chambers of commerce that 2015-16 will end with $270-billion exports, markedly lower than $311 billion in 2014-15. The government and Reserve Bank of India (RBI) have allowed the rupee to depreciate, probably to keep exports competitive. This becomes especially critical when viewed against the Chinese central bank’s repeated devaluation of the yuan — in August 2015 and again on January 7, 2016.

This then, in short, is the FM’s dilemma. How does he meet the various expenditure demands — commitment to social sector schemes; need to keep investing in public investment to rekindle economic growth; allocations to agricultural sector to forestall distress; increase in salaries, wages and pension of government employees (including the armed forces); and, finally (but most importantly), increased allocation to states from the divisible central tax pool under the Fourteenth Finance Commission award. Worse, Jaitley has to fork out increased sums of money while staring down a diminishing exchequer.

The government seems to have reached the crossroads and needs to select a path that will help it emerge from this impasse. A few ineluctable options present themselves.

Feeling Fiscy

First, will the government be willing to take the fight to fiscal conservatives? In short, will it be willing to let the fiscal deficit slip just that wee bit to fire up animal spirits in the economy?

This question goes to the heart of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) economic philosophy, which has been morphing from its avowed “swarajya” policy in the 1970s and 1980s to pro-globalisation and support for foreign investment in the 1990s. Among the many consanguineous economic ideologies that exist within mainstream BJP, its affiliates and allies (such as Shiv Sena, Vishwa Hindu Parishad) and its mother organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the umbrella right wing also includes economists of variegated hues — right-wing economists trained in Western universities (who find enlarged fiscal deficits and higher government debts anathema to the conservative notion of smaller government, low tax rates, and laissez faire economics) sitting cheek-by-jowl with free-market votaries who do not mind tweaking rules to protect domestic interests from competition (the lopsided FDI policy on foreign retail is a good example) or to suit local conditions. A lot will depend on who gets to monopolise airwaves in coming weeks.

There are other external pressures: credit rating agencies (especially the Big Two) are also wedded to fiscal orthodoxy and any deviation invites a rap on the knuckles or a downgrade, depending on the severity of the slippage. Interestingly, when the US allowed its fiscal deficit to expand to $1-trillion-plus between 2009 and 2012 — as it accelerated spending to stave off after-effects of the 2008 global financial crisis and the consequent economic slowdown — it did elicit censure from a section of Republicans in Congress, but that was pretty much it. It’s only in 2015, as the US economy continues to recover, that the deficit narrowed to $439 billion, the lowest since 2008.

Interestingly, while fiscal conservatism is considered an essential ingredient of the Republican ideological toolkit, even the Bill Clinton presidency adhered to large parts of this credo, attracting the new moniker “Liberal Democrats”. In a recent, cogent essay in The Atlantic Why America Is Moving Left, political scientist Peter Beinart, argues that President Barack Obama has pushed US economic policy dramatically to the left and it is likely to stay that way for some time to come. But, in India, conservative orthodoxy has slowly and insidiously sunk roots across ideological divides, thereby making fiscal deficits a dirty and contemptible term, even when sought to be used as a one-off, emergency measure.

There are reasons to be wary of rising fiscal deficits; the reckless borrowing and spending of the 1980s brought India close to bankruptcy in 1990. Higher fiscal deficits and swollen debt levels could jeopardise the long battle that’s been waged to achieve fiscal stability, especially when the government’s inability to control wasteful spending or to execute expenditure rationalisation is well known. Relaxing vigil on the fiscal front is like a slippery slope: reining it back requires enormous political courage.

If Jaitley, therefore, chooses to expand the fiscal gap a bit to finance all manners of expenditure (which increasingly look unavoidable now), he should expect commentators to look askance. To that extent, the FM seems to have already laid the foundation in his FY2016 Budget speech: “…insisting on, a pre-set time-table for fiscal consolidation pro-cyclically would, in my opinion, not be pro-growth…I will complete the journey to a fiscal deficit of 3 per cent in 3 years, rather than the two years envisaged previously…The additional fiscal space will go towards funding infrastructure investment.” But, between a paragraph in the budget speech and facing up to the risk lies a a wide chasm — and lots of criticism to boot.

Show Me The Money

The second tough call is raising revenue. As described above, higher tax revenues in the current economic environment increasingly seems difficult. There is no likelihood of an immediate increase in the number of tax payers which can compensate for the dip in revenues from existing tax payers. It will also be suicidal to increase tax or duty rates.

Part of the solution might lie in focusing on non-tax revenues, specifically non-debt capital receipts. The target for government disinvestment was Rs 69,500 crore and the achievement has been a paltry 18.5 per cent — Rs 12,852.90 crore. Evidently, the government’s policy of second-guessing the market has not paid off. It is also true that selling government assets in a falling market could invite Parliamentary condemnation, and the government may not wish to add this to its current list of woes. But, desperate times call for desperate measures. Jaitley might have to force the issue on this one. He does have some political capital in Delhi and he might have to expend chunks of it to push for disinvestment, regardless of how the Sensex behaves.

Another partial solution exists in the balance sheet of numerous public sector units. The government is believed to have advised profitable PSUs to pay out higher dividend this year — 30 per cent of post-tax profits or of the government’s equity, whichever is higher. There must be some number-crunching behind this. Budget FY16 estimates Rs 36,174.14 crore inflows from PSU dividends. It is to be seen if the 30 per cent dividend diktat precipitates revenue inflows higher than budgeted. There is also a likelihood that the 30 per cent decree has been necessitated by a shortfall expected in dividends budgeted from RBI, nationalised banks and financial institutions — Rs 64,477 crore. Whatever might be the reason, the government’s revenue projections for the year-end, and the anticipated resource crunch in the next year, might have necessitated the 30 per cent order.

An alternative to leveraging PSU balance sheets also exists. At last count, PSUs were sitting on a cash chest of over Rs 2,00,000 crore. Some of this has already been committed to their expansion projects. But a large part is lying idle, invested in low-yielding assets, like bank fixed deposits. The FM has to marshal these funds for a part of his public investment exercise.

A distinction might be necessary here. The PSU investible corpus should be used exclusively for creating productive assets closely aligned with the specific company’s business opportunities. Therefore, an engineering company’s cash reserves should be utilised for not only expanding existing manufacturing capacity but also creating new production capacity in the engineering industry. For example, this might be a good time to revisit India’s installed capacity for manufacturing turbines, boilers and generators. This is important because it is linked to another facet of Jaitley’s to-do list: energising Make In India. His boss, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has been busy collecting air-miles over the past 20 months, soliciting foreign investment from various governments and corporations. The trips seem to have paid off with only a slight uptick in FDI — $16.631 billion during the first half of 2015-16, a 14 per cent increase over $14.691 billion in the same period of 2014-15 — and not the deluge expected.

One reason could be the continuing stress in the developing economies, thereby inhibiting capital flows. But, importantly, the trickle of FDI could also be related to India Inc’s lackadaisical investment propensity. Many large Indian corporations have not been entirely successful in shedding investment inertia acquired during the calamitous 2009-14 UPA-II regime. Domestic industry’s unconcealed lack of confidence invariably has a demonstration effect on potential foreign investors. This needs to be corrected and a beginning could be made by asking PSUs to invest in expansion and fresh capacity, which can crowd-in fresh private sector investment.

When In Doubt, Fly

With FDI continuing to remain important for India, PM Modi is expected to retain, if not increase, his itinerant routine. Apart from crafting a fresh foreign policy doctrine for India, which seeks to project the country as a new power (or, as foreign secretary S. Jaishankar calls it, “a leading power”), PM Modi is also actively trying to drum up investments for India. He sees economic diplomacy as the centre-piece of India’s foreign policy.

But investments are only a part of economic diplomacy. Truth be told, economic diplomacy, which has a vital role in India’s desire to emerge as a “Leading” power, has twin responsibilities — opening up markets for Indian goods, services and capital (human and financial), as well as attracting foreign inward investments. In this task, he will need the unstinted support of the external affairs ministry.

The Budget, shorn of inner party rivalry, can provide the necessary strategic impetus. One of the ways in which this can be achieved is through higher allocations to successful tools of development diplomacy (such as, the highly successful Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation Programme, under which 10,000 participants from 161 partner countries visit India to attend various capacity building courses). But, more can be achieved. With economic growth showing green shoots in the US but staying tentative in Japan and Europe, India needs to find new markets for its goods and services. After the 2008 global financial crisis, India was compelled to seek out the Latin American and African markets for increasing exports. But, performance has been desultory at best. The Budget should try to correct that.

At the end of the day, the Budget is a economic policy document and not just a statement of accounts. Or, a list of tax changes. It is expected to spell out a roadmap that indicates the direction of economic policy-making and galvanises the pace of economic growth. Too many opportunities have been lost in the past with policy architects focusing on minutiae; FM Arun Jaitley has the opportunity to make enduring course corrections.

This article was published as cover story in Businessworld magazine, issue dated January 25, 2016, as part of a pre-Budget cover package titled 'A Make Or Break Budget'.

It can also be read here.

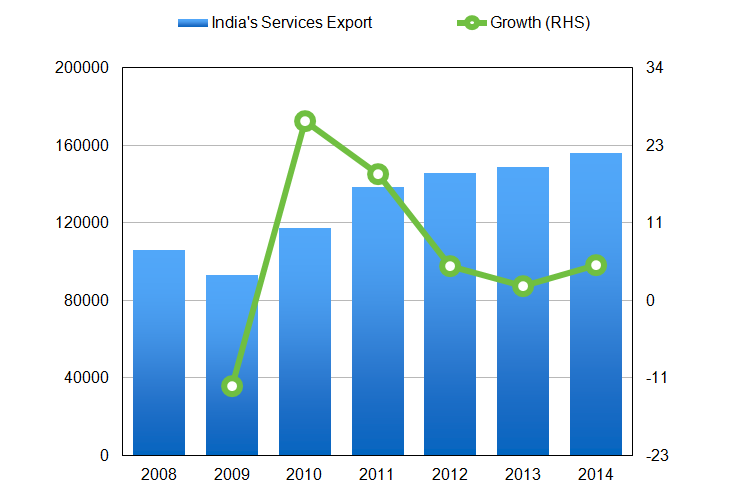

Yet, there are some oases of optimism— India’s trade in services for the first eight months of 2015-16 (April-November) showed a positive balance of $48.047 billion. In fact, this is one area in which India not only fares better than China (which has traditionally suffered a negative trade balance in services) but has also been able to stave off the China slowdown factor more effectively that merchandise trade.

Yet, there are some oases of optimism— India’s trade in services for the first eight months of 2015-16 (April-November) showed a positive balance of $48.047 billion. In fact, this is one area in which India not only fares better than China (which has traditionally suffered a negative trade balance in services) but has also been able to stave off the China slowdown factor more effectively that merchandise trade.